2025 Theme: Daily Bread

In Matthew 6:11, Jesus, in his exemplary prayer, asks God to "give us this day our daily bread." This command—written in the English in the imperative and demanding give—comes after (1) addressing deity ("Our Father which art in heaven); (2) venerating the divine ("Hallowed be thy name"); and then deferring to deity's eternal goals ("thy kingdom come. Thy will be done in earth, as it is in heaven"). The demand of Jesus to God—to provide, after deference, bread by which to eat and be filled—has been on my mind lately and is my theme for 2025.

Bread, the symbol demanded in this prayer, has come to mean many things: for the zealous and devout, it is a daily feasting upon the word of God, a practice of scripture reading or holy dedication by which to gain the spiritual sustenance for the day. It hearkens back to the manna provided to Moses and his exilic people as they traversed a wilderness barren and large. It connects to the sacramental or eucharistic bread by which believers ingest the divine, seeking connection to the savior they believed performed the greatest act for and on behalf of them.

On my Mormon mission, daily bread came to mean the morning and evening rituals by which we as representative of Christ began and ended our days. My mission president called this "striving for five." He noticed in our mission that there was a difficulty to understand how to follow the command to be "exactly obedient" to the missionary rules. He outlined the five things we were tasked with doing in the morning and the five things in the evening.* If we completed those five things, we were being exactly obedient to the missionary rules. He supplied the verb strive because, in his belief, none of us were perfect but we were all trying and thus striving to be so. I've taken this to hear in various instances since my mission, trying to create five things to do in the morning and five in the evening to feel like each day is fulfilled.

Although I am not as avid an adherent of religiosity as I was in my early twenties, I'm pulling on this idea of "daily bread" and ritual into my 2025 theme because it helps provide foundation, stability, and guidance. In The Power of Ritual: Turning Everyday Activities into Soulful Practices (2021), Casper ter Kuile argues that ritual connect you at "four levels": (1) with yourself, (2) with people around you; (3) with the natural world; (4) and with the transcendent. ter Kuile shows how daily practice becomes ritualistic by investing the sacred—here writ larger than just within a religious or spiritual way, meaning a connection to something bigger than just you—into the activities that you repeat. It isn't about the activity itself having an innate spirituality or sacredness to it; it's about the meaning you make with it (which follows a long thread of religious studies arguments, vis-a-vis the secular-sacred collapsing into one another). Thus, ter Kuile invites ritual to take a vacation, of sorts, from only spending time in the houses of religion and spend some time in the lands of the profane, quotidian, and axiomatic. And if ritual likes it there, it can stay—depending on who you are and how you live your life.

As a disclaimer, this vacation in these lands does not mean ritual isn't important to the comprehension and practice of religion. Jonathan Z. Smith, after all, declares "ritual and its capacity for routinization" to be "the sovereign power of one of the basic building blocks of religion," something very important to remember when utilizing the idea of ritual (113). By pulling ritual from the houses of religion, ter Kuile expands this "basic building block" to be one of religion, yes, and also one of humanity and humanness. Humans need—yearn for, desire, work better with—structure. For Smith, this structure—the routinization of the divine—is a foundation for religion; for ter Kuile, this routinization of the divine expands when we merge the spiritual and the profane into the quotidian (or, perhaps, invest the daily with spiritual significance).

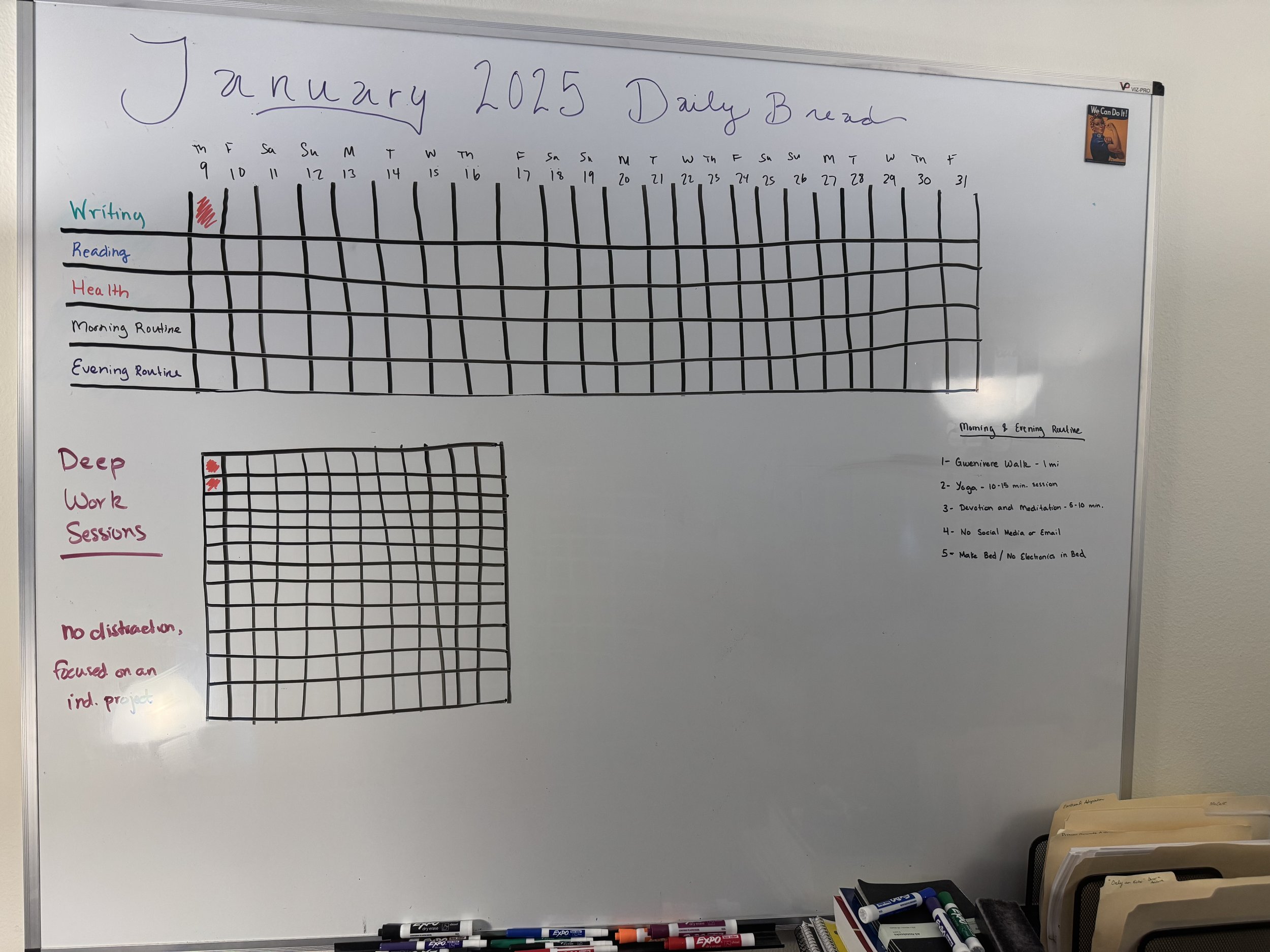

I turn to this understanding of ritual while discussing my theme for 2025 because through partaking of daily bread—through making my life more ritualized—I want to craft a daily devotional practice. For me, this begins with morning and evening routines. Pulling on my mission president's strive for five, I've tasked myself with five daily routines to invest with spiritual import. The five repeat: I do the five in the morning; I do the five in the evening.

Gwenivere Walk—walking at least one mile with Gwenivere in the morning when I wake up and in the evening when I get home from class. This latter one will be difficult because I won't be getting home until 10:30 p.m. from my classes, when all I want to do is take Gwenivere out to potty and then fall asleep.

Stretching and Health—the body ages, the body grows, and I've noticed more and more my body becoming a coiled mess. This is due, in many ways, to the layers of stress I've accumulated over the last year, but it also is because I haven't been spending as much time with my body, learning from it, teaching it, and loving it. This also encompasses daily health like vitamins, brushing teeth, and cleanliness.

Devotion and Meditation—focusing on the quiet, the stillness, the universe, and the world. A devotion could mean reading scripture or poetry, while meditation is slowing down and separating self from what is happening.

No Social Media or Email—I've gotten into the not-great habit of checking social media or my email right when I get up and right when I go to bed. I don't think find this to be helpful or to spark joy. So, I want to strive to not do either right when I wake up or when I'm preparing for bed. In this way, I want to follow the guidance of Cal Newport in Digital Minimalism: instead of having social media/email be a constant presence, limiting it to strict times (in some ways, an anti-ritual).

Make Bed / No Electronics in Bed—The first one is a freebie, in sorts, since I always make my bed in the morning (it's the one things I do consistently in my chaotic life). The latter, no electronics in bed, is a desire to make my bedroom into a sacred place of rejuvenation. My goal is not have my phone—nor my tablet/kindle—in the bed. I want to be finished with reading and engagement outside the bedroom, leaving the bed as the place to focus on recovering to face the horrors yet again the next day.

My other formulation of daily bread is five things to do each day that will make each day feel complete. These habits are (1) writing; (2) reading; (3) living; (4) morning routine; and (5) evening routine. Since I've discussed the fourth and fifth, I'll emphasize the first three here.

Writing is the lifeblood of what I want to do in life. Whether its academic articles, personal essays, or fictionalized stories, I think, I articulate, and I, ultimately, exist through writing. No matter where my life leads me—currently, as an embryonic academic—I want writing to be a daily practice.

Writing cannot be done without reading—and I think it's clear how much I love reading. Reading for me takes many forms: listening to audiobooks or AI reading apps like Speechify; reading emails or essays; taking in the news in all its forms from podcasts to articles. For this habit, though, I want to emphasize a deep reading practice: taking time to sit and read for an hour, with my commonplace book next to me. I want to follow, in some ways, the monk-like practice that Cal Newport discusses in Deep Work, in which he would turn off his academic day job through a closing ritual and then spend much of his evening reading.

Living, of course, will occur throughout all of this year (God willing). When I place the word living, I mean doing something every day related to health—whether that be physical, social, mental, emotional, etc. "Healthing" isn't a real word, so I went with "living," but I think it fits for my desire: intentionally doing something that reminds me that I exist in a very physical way.

So, essentially, then, my desire in claiming the theme "daily bread" is to ritualize my mornings and evenings, while also investing my other habits—writing, reading, and taking care of my health—with spiritual import.+

Adam’s trusty white board that helps them stay on their rituals.

Footnotes

* Morning activities were (1) wake by 6:30 a.m.; (2) exercise for 30 minutes; (3) one hour of personal study; (4) one hour of companion study; (5) out the door by 10 a.m. Evening activities were (1) home by 9:00 p.m.; (2) daily planning for 30 minutes; (3) journal ; (4) pray; (5) bed by 10:30 p.m. I can't quite remember if three and four of the evening routine were the same, but it's a rough estimate of it all.

References

Cal Newport, Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World. Grand Central, 2016. (See also Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World, Portfolio, 2019 and Slow Productivity: The Lost Art of Accomplishment Without Burnout, Portfolio, 2024)

Casper ter Kuile, The Power of Ritual: Turning Everyday Activities into Soulful Practices. HarperCollins, 2021.

Jonathan Z. Smith, "The Bare Facts of Ritual," History of Religions 20, no. 1/2 (1980): 112–127.